From The Struggle Is Our Inheritance

Minnesota erupted in an armed conflict in 1862 between Dakota warriors and the United States. The conflict left in its wake between 300 and 800 settlers dead, an unknown number of Dakota dead, and the largest mass execution with 38 Dakota men hanged at Mankato. This was the first armed conflict between the Dakota and the United States, but it would not be the last.

This is a particularly important event for me as my ancestors and my relations were Dakota in Minnesota. Being both a descendant of the original people of this land and a person working against the imperialist culture occupying it, I find the history of this struggle to be extremely important for the work I am to do.

The Dakota Uprising of 1862, as it has come to be called, began with the Treaty of Traverse de Sioux and the Treaty of Mendota in 1851. These treaties, which were signed by a few Dakota men intoxicated by whiskey, ceded vast amounts of Dakota territory to the United States. The treaty guaranteed the Dakota money, food, goods, and a twenty-mile wide reservation along a 150-mile stretch of the Minnesota River. The treaty became null and void after promised compensation was either never given or stolen by officials in the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

When Minnesota was declared a state in 1858, representatives of several bands of Dakota, including Chief Taoyateduta, traveled to Washington, D.C. to make further negotiations. The negotiations resulted in the Dakota losing the northern half of the reservation along the Minnesota River along with rights and access to the sacred Pipestone quarry. The ceded land was quickly split up into several townships and farmland for settlers. This resulted in the wild prairies, forests, and wild lands, used for traditional lifeways, being destroyed. Traditional lifeways were so devastated by colonial settlement that Dakota people in south and western Minnesota had to sell fur pelts to make a living.

Payments guaranteed by treaties were never made. The populations that had supported Dakota communities were nearly wiped out. Land was being stolen by the United States government and occupied by settlers. Additionally, broken treaties, food shortages, and famine all added to growing tensions.

On August 8, 1862, representatives of the Sisseton and Wahpeton bands of Dakota successfully negotiated for food in the Upper Sioux Agency. However, the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dakota turned to the Lower Sioux Agency with the same demands and were denied food. Indian Agent and Minnesota State Senator Thomas Galbraith would not distribute the food without payment, and lead trader Andrew Myrick responded to the Dakota by stating, “So far as I’m concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass.”

Three days later, Andrew Myrick was found dead, grass stuffed in his mouth. Chief Taoyateduta had led a band of warriors to attack settlers in the Lower Sioux Agency. Food stores were taken and several buildings were burnt to the ground. A militia that was sent to suppress the uprising ended up suffering 44 casualties and losing the Battle of Redwood Ferry. The Dakota band continued to attack the settlement and New Ulm and then mounted an attack against Fort Ridgley on August 22.

Raids on farms and settlements continued throughout south and central part of Minnesota. Counter-attacks by Minnesota troops resulted in heavy casualties of white soldiers at the Battle of Birch Coulee. Thirteen United States soldiers were killed and over 47 were injured. The Dakota only suffered two deaths.

In northwestern Minnesota, Dakota warriors attacked several trail stops and river crossings along the Red River Trail. This stopped trade along this route to forts further west. Mail carriers, stage drivers, and military transports were all attacked between Fort Snelling and St. Cloud. Abraham Lincoln was finally forced to assemble troops from the Third and Fourth Minnesota Regiments.

Governor Alexander Ramsey formulated a plan, carried out by Colonel Henry Sibley, to free settlers held captive and to “exterminate” or otherwise drive the Dakota “forever beyond the border of the state”. Sibley’s troops ranked in around 1,600 men, while the Dakota only had around 700 warriors.

The fighting lasted over six weeks. Most of the major fighting occurred at the Battle of Wood Lake in September, where Taoyateduta attempted to ambush soldiers of the Third Minnesota Regiment marching along the Minnesota River. The soldiers returned fire and were quickly aided by other soldiers from Sibley’s camp. The fight lasted two hours with the Dakota warriors suffering heavy losses. This would be the last major battle fought in the Dakota War of 1862.

Dakota warriors ended up surrendering at Camp Release on September 26. Six weeks later, 303 Dakota prisoners were convicted of rape and murder and sentenced to death. There is much reason to believe that these trials were heavily biased, most of them lasting only five minutes. Lincoln reviewed trial records and distinguished between those who fought and those who he believed had been part of the murders and rapes. Thirty-eight who had been part of the latter were hanged in Mankato on December 26, 1862. The remaining convicted Dakota stayed in prison that winter and were later transferred Rock Island, Illinois where they were imprisoned for four years. Over one third died of disease, and the remaining returned to their families that had been relocated to Nebraska, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas.

As a result of the conflict, the United States abolished the reservations, declared all treaties null and void, and expelled all Dakota from Minnesota. A bounty of $25 per scalp was placed on all Dakota men, women, and children within the state’s boundaries. The only exceptions were several groups of Dakota referred to as the “friendlies” who allied themselves with the white settlers and were allowed reservations, such as the Shakopee Mdewakanton Dakota.

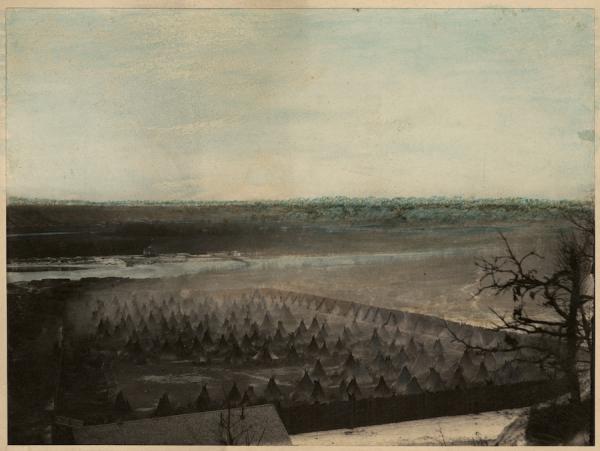

During the winter of 1862-63, around 1,700 Dakota were rounded up into concentration camps on Pike Island below Fort Snelling. Only 1,300 Dakota left the following spring, and were exiled to surrounding states. The others had died or been killed in the camp. It is believed there were mass graves located near this site and the site of the current Mall of America. It is also believed that four oaks were later planted in the contemporary Minnehaha Park to commemorate those who died. The four oaks were planted in each cardinal direction in the shape of a burial scaffold used to mourn the dead.

While many Dakota were exiled from Minnesota into the surrounding areas, many eventually returned and found their ancestral territories turned into settlements and townships. They reestablished several smaller reservations; however, many assimilated with the white settlers and attempted to obscure their identities while others braced themselves for the harsh realities of colonialism and attempted to maintain their traditions.

The Dakota War of 1862 was the beginning of a long period of resistance by the Dakota and Lakota nations against United States imperialism. It was followed by the Battle of Killdeer Mountain in 1864. Red Cloud’s War in 1866-68 resulted in a complete victory for the Oglala Lakota and the preservation of their control of the Powder River country. The Battle of Greasy Grass in 1876 was another victory for Lakota and Cheyenne, which saw the complete annihilation of a U.S. detachment led by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. The last major conflict was the Wounded Knee Massacre in which over 300 Lakota men, women, and children were gunned down by the brutal U.S. 7th Calvary.

For me, this story is filled with both honor and pain. While the conflict resulted in the removal of my ancestors from their territory, it makes me proud to know that my relations fought against this colonization. Many of the Dakota people assimilated, but there were some who held on to their traditions for a future generation who might reclaim their lifeways and territories. As for this story, it serves as a clear indication of where I am to stand in the struggle for this land.