From The Struggle Is Our Inheritance

The University of Minnesota opened its West Bank campus in the early 1960s. By the end of the decade, the neighborhood had changed from one of mainly Scandinavian immigrants to one comprised largely of students and members of the white youth counterculture. During the same time, Keith Heller, a professor at the University, was quietly buying up land in the area. His plan was to raze the neighborhood and build ten high-rise apartment buildings in its place. This project was going to be called “New Town in Town.”

The University of Minnesota opened its West Bank campus in the early 1960s. By the end of the decade, the neighborhood had changed from one of mainly Scandinavian immigrants to one comprised largely of students and members of the white youth counterculture. During the same time, Keith Heller, a professor at the University, was quietly buying up land in the area. His plan was to raze the neighborhood and build ten high-rise apartment buildings in its place. This project was going to be called “New Town in Town.”

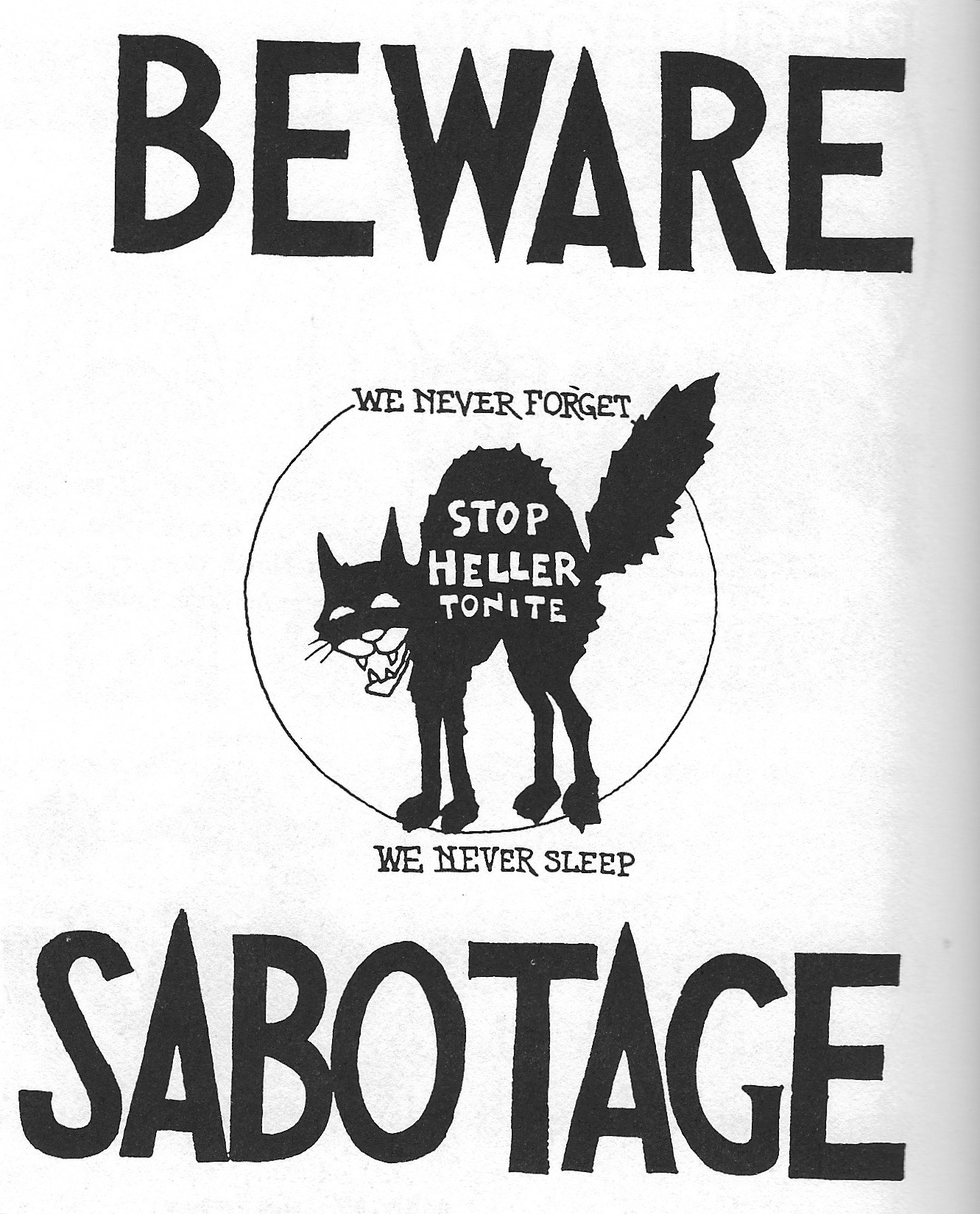

Needless to say, residents of Cedar-Riverside weren’t exactly thrilled with the looming prospect of their houses and community being replaced with a maze of intensely developed high rises. At a public hearing on the plan, 400 people showed up to oppose the plan. But despite their anger, the plan passed. Heller’s inside connections probably helped nudge HUD (Housing and Urban Development) to waive certain policies, and the development was approved and funded. The project was to be built in ten phases. Housing organizers, including the Minnesota Tenants Union, fought the Cedar-Riverside complex with both demonstrations and environmentally related lawsuits.

At the same time, residents were creating a community worth saving. A Community Union was formed, as well as a free clinic (the Cedar-Riverside People’s Center) and the collectively run New Riverside Café. Folks began publishing a community newspaper called, “Snooze News”. In the neighborhood, vacant lots were turned into parks and marked with hand painted signs. Multiple organizations fighting New Town were formed, some of which existed as fronts to navigate through the bureaucracy of the housing authority.

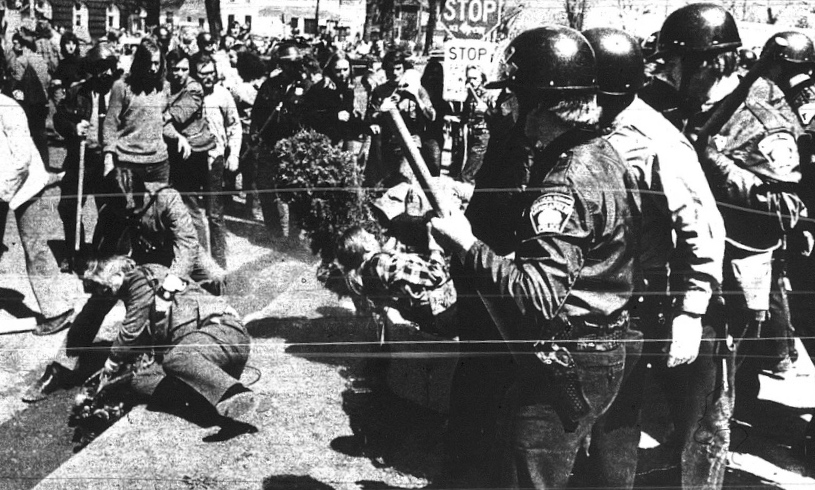

As the first stages of the plan were completed, producing several high rises, the community continued to mobilize. George Romney, the secretary of HUD, was invited to come up from Chicago for the opening ceremony. Heller’s corporation, Cedar- Riverside Associates (CRA), went around sprucing up the neighborhood, painting the fronts of houses and planting geraniums on the corners they knew Romney’d have to turn. New Riverside Café collective members held an impromptu stenciling extravaganza the night before, proclaiming, “This neighborhood is being ‘REDEVELOPED’ with no concern for the residents or environment.” The dedication that day was also the site of an anti-war demonstration, and a battle between the police and eggs, rocks, and marshmallows. Romney ended up deciding it was too dangerous a situation and that he’d be unable to attend the opening ceremony.

Opposition to the plan fermented in the mid-70s, when hundreds of tenants in the neighborhood simultaneously received a notice of rent increases. Cedar-Riverside Associates owned most of the houses in the area, and as opposition grew and the success of the New Town plan grew dim, CRA struck out with rent hikes of as much as 50%. A community meeting was called, which a few hundred people showed up for. There they decided to form a tenants’ union and begin a rent strike. The group formed a Negotiating Team, which was responsible for most of the organizing work. Frequent big meetings, in which decisions were made by discussion and debate, ensured that the team remained accountable to the residents.

The group, calling themselves the E ast-West Bank Tenants union drafted a response letter to the increase notices that stated, in part:

“We find it necessary to refuse to pay exorbitant rent increases or vacate our homes…We can not honestly state that we value your landlordship as you say you value our tenancy. It is we, after all, who are paying your bills. Should you see fit to carry out your threat of mass eviction contained in the ‘offer’ you gave us by evicting even one tenant, we will find it necessary to terminate your tenancy in our neighborhood.”

The strike ended a few months after it began, with most of the rents returning to their original levels, and written leases where previously there had only been oral agreements. Occasional rent strikes continued through the early 80’s. Tenants of the first high rises also went on strike over rent increases. The strikes and lawsuits eventually helped to bankrupt the development company, and most of the housing was either sold off as co-ops or received project-based Section 8 subsidies. Only the first stage of the development project—the few multi-colored high-rises that are a trademark of the West Bank scenery—was completed. Today these house primarily Somali immigrants.