From The Struggle Is Our Inheritance

An interesting example of popular sabotage was born in Minnesota during the late 1970’s. It was here that a group of farmers in Western Minnesota perfected the art and science of toppling high-tension electrical towers. After federal agents began investigating these incidents, the farmers would only reply, “Hmpf…Must’ve been those bolt weevils.”

The trouble began when United Power Association and the Cooperative Power Association were looking to exploit coal reserves in North Dakota and needed a 453-mile transmission line through Minnesota farmland to the industrial center of the Twin Cities. As is typical, poor people were screwed so that rich corporations could benefit. Most of the electricity would be used by industry, not people. The utility corporations chose to plan power lines through land belonging to poor farmers rather than huge corporate farms.

What these corporations did not expect was opposition. And that is just what they received.

Virgil Fuchs, one of the farmers, became aware of what this would mean for the small farmers. The plans would require strips 160-feet wide cut through their fields, and 180-foot pylons erected to support the wires. The health problems associated with electromagnetic pollution (from the currents running through these power lines) were also a concern. It was already known that electrical lines lower conception rates and milk production in dairy cows. And the state’s own guidelines warned farmers against refueling their vehicles under the transmission lines and warned school bus drivers against picking up or discharging children under them.

Fuchs went knocking door-to-door at his neighbors’, informing them of the plans. Soon after, corporate representatives were on his tail trying to get farmers to sign agreements, but not one farmer signed.

Local townships soon passed resolutions disallowing the power lines, and county boards refused to give permits for the power line construction. The corporations planning the construction ignored the local concerns and turned to the state. The farmers also turned to the state looking for help from their “representatives.” The state’s Environmental Quality Council responded by holding public hearings. The public opinion at the meetings ran overwhelmingly against the power lines, but these unfavorable testimonies were left out of the transcripts.

Throughout the years 1974 to 1977, farmers tried lengthy and ineffectual legal channels such as these to block the construction. They were only permitted to request that the construction happen on someone else’s land, rather than their own.

Not surprisingly, the state granted the permit for the construction in 1977. One county attempted to sue, but the case was dismissed. At the very least, government representatives promised they would let the farmers know when construction was to begin. But again, they lied.

When surveyors showed up in Virgil Fuch’s fields, he fought back. He drove his tractor over the surveyors’ equipment and rammed their pickup truck. Farmers from across the counties began gathering and planned to fight the surveyors any way they could. Such tactics included getting permits to tear up roads, and running chainsaws or other loud equipment so that the surveyors couldn’t communicate. The network of farmers that had formed through legal battles helped to increase the resistance to the construction. When surveyors would show up to begin work, hundreds of farmers would block their way.

Even the local sheriff was sympathetic. “In my opinion this is a situation that began with the Environmental Quality Council, at the request of the power companies, and that’s where the problem should be remanded for resolution. I will not point a gun at either the farmer or the surveyor. To point a gun is to be prepared to shoot, and this situation certainly does not justify either. It does justify a review of the conditions that bring about such citizen resistance.”

It also seemed as if Philip Martin, the head of United Power Association, sympathized too. He had grown up on a farm and had even known Virgil’s mother. He had said of her: “She reminded me somewhat of my own mother.” But that did not stop his decision that would affect so many small family farmers.

It seems to make sense why Martin was so upset. In North Dakota, they had only faced one protester and dealt with him quickly. In Martin’s own words: “The law enforcement there initiated the action to put him in prison, or jail. And pretty soon he said, ‘I’ll be a good boy, I won’t do any more,’ and they let him out, and we built a transmission line.”

However, in Minnesota: “The law enforcement refused to enforce their own laws. We could go out and try to survey, and they would simply pull up all our stakes, they would destroy everything we had out there. And there was never anything done.”

The farmers continued to file lawsuits, which ended up going to the Minnesota Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court decided against them. This act radicalized many of the farmers.

More than 60 percent of Minnesotans supported the farmers against the power line. However, they were outmatched by the power companies’ lawyers and technical experts. In the end, state government and the courts took the companies’ side.

In the winter of 1978, the confrontations in the fields would span weeks, and governor Perpich sent in nearly half of the highway patrol. Many of the cops who had been sympathetic turned against the farmers and told them that they couldn’t assemble, couldn’t drive on county roads, couldn’t stop on township roads, etc. When confronted about this, cops stated, “We will do whatever we can to get that power line through.”

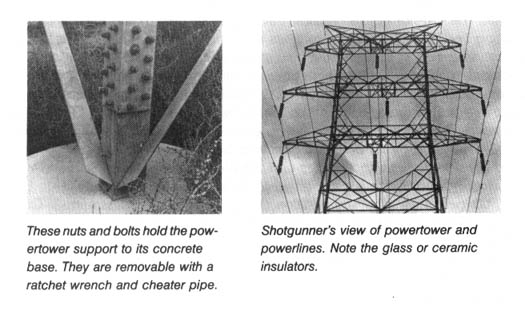

In August 1978, a 150-foot steel transmission tower came crashing to the ground. Upon inspection, authorities found that the bolts of the base had been loosened. Over the next few weeks, three more fell down. Guard poles had been cut in half, step bolts had been cut three-quarters through, bolts at the base were loosened or removed, and insulators were shot out.

Minnesota Public Radio reporter Greg Barron visited West Minnesota and described the situation as nothing short of “guerilla war.” Helicopter crews patrolled 170 miles of power lines, and squad cars combed the countryside. The governor eventually called out the FBI to help conduct heavy surveillance.

Seventy-two arrests were made in just one county. Six of these were for felony charges. Everyone refused to testify against the farmers arrested. The only information the cops got from farmers was the response, “Hmpf! Must be the bolt weevils.” And even though two farmers were eventually convicted of felonies, they were only sentenced to community service.

An interview with dairy farmer Tony Bartos revealed the sentiments of most the farmers:

“Yeah, I go along with it. I wish a few more would come down, and I think they will, as time goes on. They shouldn’t have did this to us in the first place. We’ve did everything we could lawfully. We went to Minneapolis, got lawyers, went through the courts. But either the judges are paid off, or they just don’t realize what’s going on out here. I think there’s a lot of different laws and ways you can look at it. There’s moral laws, too. I don’t know, I don’t figure it’s wrong what we’re doing out here. Sure people think you gotta stay with the law, but what is the law? Who makes it? We should have more of a say with what goes on in this state too, you know. They can’t just run over us like a bunch of dogs.”

The power line was constructed, and operations began in 1979. Despite this loss, an impressive wave of sabotage continued to hit the power line. Within only two years, fourteen towers were toppled, and over 10,000 insulators were shot out. The project could only continue after the energy corporations turned ownership over to the U.S. government. This was a direct result of the economic losses caused by sabotage and the costs of security. Even with this turnover to the State, a fifteenth tower was toppled on New Year’s Eve in 1981.

Many lessons can be drawn from the experiences of those who fought against this project. Legal channels only revealed that in the eyes of the State, industrial development would always take priority over the healthy and livelihood of its citizens. As a result, a social struggle manifested and directly attacked the source of the problem. Sabotage proved to be far more costly to the energy corporations, and direct action was a manifestation of public sentiments, especially the sentiments of those most ill-affected by the project.

The following guidelines on monkey wrenching power lines come from anonymous Bolt Weevil veterans:

Power lines are highly vulnerable to monkey wrenching from individuals or small groups. The best techniques are: 1) removing bolts from steel towers; 2) if tower bolts are welded to the nuts, steel towers can be cut with hacksaws, cutting wheels, or torches (be careful not to breathe the vapors of galvanized metal); 3) shooting out insulators (a shotgun works best) or shooting the electrical conductor itself (use a high-powered rifle) which frays it and reduces its ability to transmit electricity.

Chain saws (or crosscut saws work when noise is a problem) are appropriate for the large wooden towers. Otherwise, techniques that connect the conductors directly to each other are also effective (cable lifted by balloons or shot by harpoon guns). But be warned: these are more dangerous to ecoteurs. These techniques can completely baffle the opposition if used creatively. Most power line towers are attached to a concrete base by large bolts and nuts (with or without the addition of guy wires). Check the size of the nuts, get a socket set for that size nut, a cheater pipe for better torque, and remove the nuts. You may also want to tap out the bolts with a hammer. Wind will do the rest after you are safely away from the area.

The more vulnerable towers are those spanning a canyon, at corners, on long spans, going up or down mountains. Any place there is added stress or powerful wind. The “domino effect” can be achieved by monkey wrenching a series of towers leading up to a corner or otherwise stressed tower, and then monkey wrenching the stressed tower. Be prepared: a monkey wrenched, stressed tower will probably come down in your presence.

If the nuts are welded to the bolts to prevent removal, use a hacksaw to cut through the bolts or even through the supports. This is more difficult, but a night’s work can still prepare a good number of towers for toppling in the next storm.

A cutting torch can also be used for cutting through tower. Keep in mind that use of a cutting torch may result in additional arson charges. This has happened with a case in Arizona.

Another effective method, where noise is not much of a problem, is to shoot out the insulators holding the power cables themselves. A twelve-gauge shotgun loaded with double-ought shot is the best tool. Walk under the line until you are directly beneath the insulators on a tower. With your back to the wind, take two large steps backwards, aim at the insulators, and commence firing. Be prepared to dodge large chunks of falling glass.

Large power lines are suspended from strings of 20 or more insulators. Breaking 70 to 90 percent of them in one string is usually enough to ground out the conductor. This may take several rounds (the record is two), and will cause bright sparks. A team of three shotgunners, each taking a string of insulators for one conductor or conductor bundle, is best for a typical AC line. The lines are seldom shot through and fall, but stay alert for this possibility. Keep in mind that the use of firearms will result in additional charges if you are caught.

When insulators are shot out, the line quits carrying power and has to be shut down until the point of disruption is found and repaired. A helicopter may have to fly several hundred miles of power line to find where it has been monkey wrenched. Monkey wrenching at a number of locations on the same night compounds the utility company’s problems.

Because of the noise from the use of shotguns, extreme security measures are necessary and several escape routes should be planned. Furthermore, the use of firearms makes this a potentially dangerous activity. Do not leave any empty shotgun shells at the scene, since they can be positively traced to the gun that fired them.

Smaller power lines are vulnerable to having their insulators shot out by a .22 rifle from a car or a hiker. (“Power line? What power line? I’m just hunting rabbits.”) This is an effective way to discourage power companies from spraying rights-of-way with toxic herbicides if you let the power company know that the damage is being done because of herbicide spraying and that it will stop when they stop poisoning the area.

Field Notes

One item in Murphy’s Law states, “When loosening bolts, one of them is bound to be a roller (a bolt that will not simply spin off, but must be wrenched off millimeter by millimeter). It will either be the last bolt or the one most difficult to reach.

So, for the soloist, it is wise to carry a cheap 3” C-clamp (which can be bought at any hardware store) and a flat box-end wrench. Put the “fixed” head of the C-frame on the outside of the angle iron (the flat side) of the power tower and the floating head of the screw on the inside (sloped face). This gives you a brace to hold the box wrench so you can use both hands on the ratchet. This set- up will sometimes slip, so be careful to avoid skinned knuckles (wear gloves). An off-set wrench will only roll off the nut, adding to your frustrations.

Guy wires support some power line towers. It would be extremely dangerous to cut the guy wires. They are under great tension and the resulting snap could easily kill a nearby person. Also, the tower would be quite unstable after the last guy wire is cut – there is no telling where it would fall.

A safer method is to use a 4 foot long bar on the turnbuckle connecting the guy wire to ground and just unscrew the sucker most of the way. Let the wind do the rest-do not unscrew it all the way or you will be in the same danger as from cutting the wire.

Power lines are generally patrolled at least once a week at irregular times.

Any work near power lines or other sources of electricity must be done with extreme caution. The high voltage will kill you if you are careless. If you have the opportunity, watch a power company crew doing “Hot Stick” work. If you must work around live wires, use proper equipment.

According to a recent report from UPI, utility companies are warning the public that small, metallic balloons (such as those sold for birthday parties and Valentine’s Day) have been implicated in several recent power failures. “In the past couple of years these metallic balloons have come up from nowhere and have escalated into a major source of power outages,” said Harry Arnott, a spokesman for Pacific Gas & Electric, a major California utility.

The Mylar balloons have a 1000th-of-an-inch coating of aluminum, which is an excellent conductor of electricity. When a stray balloon gets caught between two power lines, it can cause electricity to arc between the lines, melting the lines and sometimes blowing up transformers and causing live wires to fall to the ground.

In 1987, PG&E blamed balloons for 140 power outages, while Southern California Edison reported 229 balloon-caused outages. An outage on Valentine’s Day in 1986 caused by a silvery heart balloon affected 20,000 customers. A balloon-caused outage in Antioch, California, in August 1987, affected 2750 customers and fried wires in microwaves, VCRs, and TV sets. The problem caused by holiday balloons has only been recognized recently, because the balloons usually disintegrate when they hit power lines, leaving no trace.